The Monastery of Mor Lo´ozor

per person

Mor Lo’ozor Monastery is on the top of a hill, few kilometers from the village of Mercimekli (Syriac Habsenas) north of Midyat. The British historian Andrew Palmer claims that it was founded by Shem‘un, the son of Mundar of Habsenas, who died in 734 (Palmer, Andrew. ‘La Montagne Aux LXX Monastères. La Géographie Monastique Du Tur ’Abdin’. In Le Monachisme Syriaque, 169–259. Études Syriaques 7. Paris: Librairie orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 2010: 34). Moreover, the construction techniques of some parts of the religious might date back to the 5th and 6th centuries (Hollerweger, Hans, Andrew Palmer, Sebastian Brock, and Sevil Gülçur. Lebendiges Kulturerbe : Turabdin : Wo Die Sprache Jesu Gesprochen Wird. Freunde des Tur Abdin, 1999: 138-139).

Not much is known, unfortunately, about its vicissitudes within the history of the Ṭūr ‘Abdīn region, besides the fact that it flourished around 1500, though it wasn’t mentioned in the Ottoman tax-registers of the sixteenth century (Göyünç, Nejat. ‘Ṭūr ‘Abdīn Im 16. Jahrhundert Nach Den Osmanischen Katasterbüchern’. Zeitschriften Der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Deutscher Orientalistentag, Supplement II: XVIII, 1972: 142–48.). In 1865 it was rebuilt ‘after lying in ruins for many years’ (Barsawm, A. Catalogues of Syrian Orthodox Manuscripts, in Syriac and Arabic. Edited by Z. Iwas. Vol. 1 Tur Abdin. 3 vols. Damascus, 2008: 377, 499), and now it lies in ruins again, for it has long been devoid of monks and uninhabited. Therefore, Mor Lo’ozor would highly benefit from academic and media attention, including a proper analysis of the complex and its historical richness, that could foster and enable the authorities to restore it and prevent it from disappearing.

FORMAL ANALYSIS

The archaeologist Barış Altan points out that the use of large cut-stone blocks (about 2 meters wide)in the southern wall indicate either an earlier structure or spolia (Altan, Barış. ‘Monastery of Mor Loʿozor’. In Syriac Architectural Heritage at Risk in TurʿAbdin, edited by Elif Keser Kayaalp, 66–69. Istanbul: KMKD, 2022: 66).

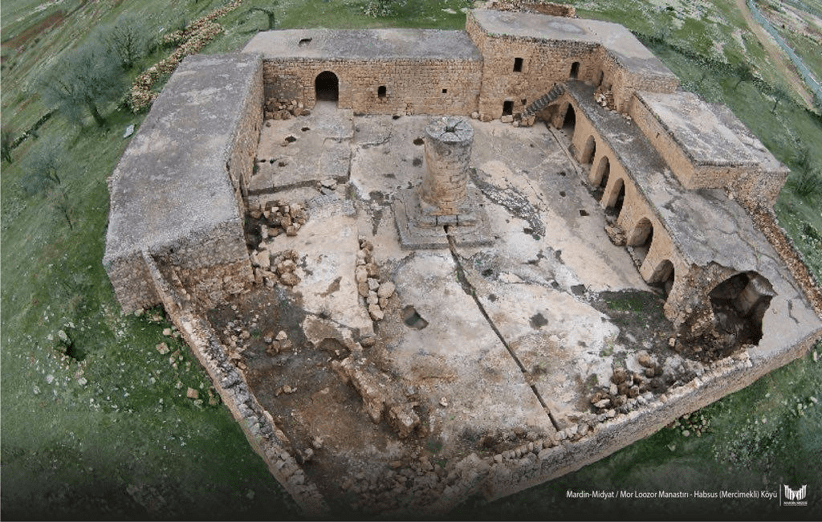

The monastic complex occupied a squared area of around 20 meters per side, surrounded by a three-meter-high stone wall, with the entrance door sited on the left corner of the west wall. It supposedly still preserves its original structure and appearance. The main door leads to a closed porch, and it is understood from an undated inscription on the door that the porch was built by Priest Yusuf as a later addiction (Cr, Şükran. ‘Mor Lo’ozor Manastiri’. Mukaddime 2, 2010).

The main courtyard of the monastery is entered through a round arched door opened from the northern wall of the porch. On the east side of the courtyard, there is a section rising with pointed arched columns, and behind it is a very small and modest church, considering the size of the monastery, the floor of the courtyard is natural rock. Unfortunately, a large part of Mor Lo’ozor south wall was destroyed and damaged due to long-term disuse and neglect (Yaşar, 2010).

There are large rooms on the west side of the monastery, made of regular cut stone, which probably housed the monks. Considering the size of the rooms, it might be inferred that a number from eight to ten priests could comfortably stay in each room. Unfortunately, these rooms were randomly excavated by treasure hunters and the floor was destroyed. The building located in the northeastern part of the monastery has two floors, accessed from the courtyard by a staircase made of cut stone.

What makes Mor Lo’ozor Monastery special in the Ṭūr ‘Abdīn region is the stylite tower in its courtyard. This architectural type, despite being well testified by written sources, has been preserved only in another site, i.e., Dayr Stūne (Dayro d-estuneh) near Nisibis. The column of Mor Lo’ozor requires further attention as it is a unique example of a masonry stylite’s tower, for it is constructed in cut-stone courses while other seclusion towers are rather built of monolithic stones, Mor Lo’ozor tower has a hole in the middle, that connects with the channels on the rock surface of the courtyard. Its outer diameter is about 2.5 meters, and its height is about 7 meters (Altan, 2022: 66-7). Furthermore, it is a particularly interesting element also by virtue of having been built in the eighth century, when the region was under Arab rule (Keser Kayaalp 2021: 194). Unfortunately, the upper part of this tower, which was built of cut stone on a four-step pedestal, was destroyed (Yaşar, 2010).

The church in the monastery, as previously mentioned, is modest and small compared to the size of the monastery. It is a north-south oriented structure with a bipartite square plant. One half constituted the ritual section and the other was the community area, and the two spaces communicated through two entrances (Yaşar, 2010).

There is a number of caves in the northwestern part of the monastery, artificially cut into the rocks. These caves have a rectangular shape and are about two- or three-square meters wide. Some of them contain large amounts of human bones, showing that they were used as burials for some time. Since no records were found in these caves, we cannot say anything about the nature of the graves (Yaşar, 2010).

VIRGINIA SOMELLA, BILKENT UNIVERSITY

- THE MONASTERY OF MOR LO’OZOR THE MONASTERY OF MOR LO’OZOR THE MONASTERY OF MOR LO’OZOR © PHOT. ARAMESE FEDERATIE NL ON TWITTER

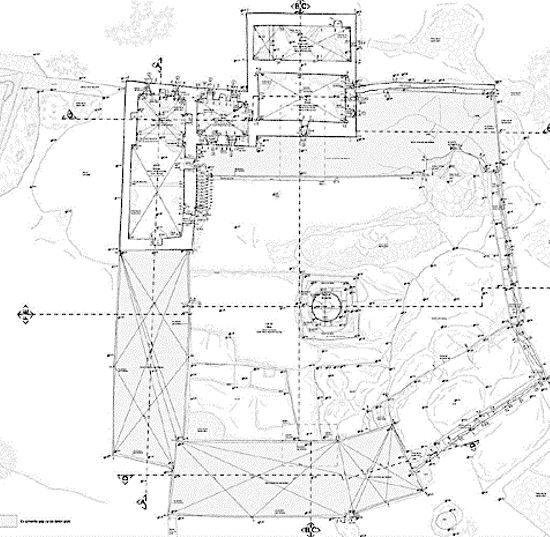

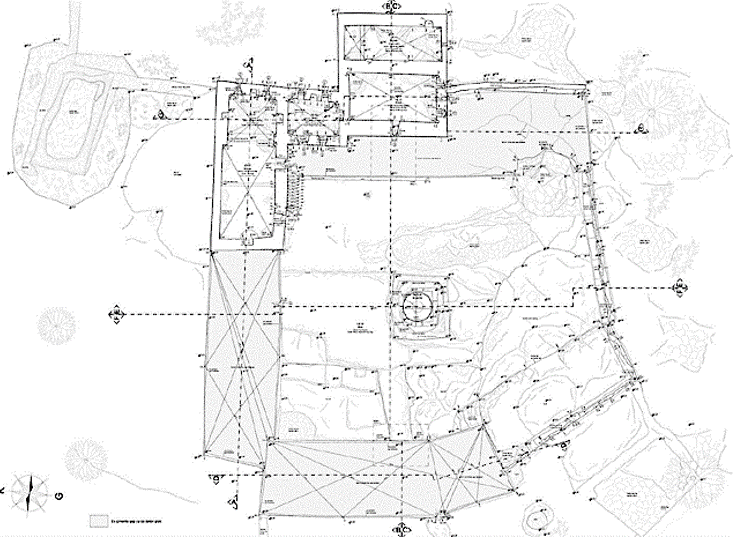

- THE MONASTERY OF MOR LO’OZOR © PLAN. MOR LO’OZOR MONASTERY, LAYOUT WITH CONTOUR LINES Altan, Barış, 2022: 68

- MOR LO’OZOR MONASTERY © PHOT. Altan, Barış. ‘Monastery of Mor Loʿozor’. In Syriac Architectural Heritage at Risk in TurʿAbdin, edited by Elif Keser Kayaalp, 66–69. Istanbul: KMKD, 2022: 67

- INTERIOR WALL OF THECHURCH’ SHORT SIDE © PHOT. VIRGINIA SOMMELLA, 2019

- NARROW OPENING ON THE EASTERN WALL OF THE CHURCH SANTUARY, TO BENEFIT FROM DAYLIGHT © PHOT. VIRGINIA SOMMELLA, 2019

- ENTRANCE TO THE CHURCH’ SANCTUARY © PHOT. VIRGINIA SOMMELLA, 2019

- DETAIL OF A NICHE © PHOT. VIRGINIA SOMMELLA, 2019

- COURTYARD AND NORTHERN PORCH, PARTIALLY COLLAPSED © PHOT. VIRGINIA SOMMELLA, 2019

- COURTYARD AND ENTRANCE TO THE SOUTHERN ROOMS © PHOT. VIRGINIA SOMMELLA, 2019

- INTERIOR SPACES © PHOT. VIRGINIA SOMMELLA, 2019

- RESERVOIR AND CHANNEL, UNDATED. IN THE FOREGROUND, THE DRAINPIPE CUT INTO THE ROCK BANK ON WHICH THE MONASTERY IS BUILT © PHOT. VIRGINIA SOMMELLA, 2019

- IN THE FOREGROUND, THE DRAINPIPE CUT INTO THE ROCK BANK ON WHICH THE MONASTERY IS BUILT © PHOT. VIRGINIA SOMMELLA, 2019

- REMAINS OF THE LOWER PART OF THE STYLITE TOWER WITH CIRCULAR SECTION, AT THE CENTER OF THE INNER COURT © PHOT. VIRGINIA SOMMELLA, 2019

- AOPROACHING THE MONASTERY OF MOR LO’OZOR FROM THE VILLAGE OF MERCIMEKLI © PHOT. VIRGINIA SOMMELLA, 2019

Tour Location

The Monastery of Mor Lo´ozor

| Other monuments and places to visit | Church of Mor Shemun at Mercimekli (Habsenas). |

| Natural Heritage | Hilly region at the southern edge of the Anatolian Plateau, the land is fertile towards the stream and various fruit trees are grown, mainly olive. Probably this area belonged to the monastery, it was the places where agriculture was done. |

| Historical Recreations | |

| Festivals of Tourist Interest | |

| Fairs | |

| Tourist Office | Yes |

| Specialized Guides | Yes |

| Guided visits | Yes |

| Accommodations | Hotel or bed and breakfast in the cities of Midyat (3 min by car) or Mardin (1 h by car). |

| Restaurants | Restaurants in the city of Midyat (3 min by car). |

| Craft | |

| Bibliography | T. A. Sinclair, Eastern Turkey: An Architectural and Archaeological Survey., 4 vols (Pindar Press, 1987). Andrew Palmer, Monk and Mason on the Tigris Frontier: The Early History of Tur `Abdin (Cambridge England ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990). Hans Hollerweger et al., Lebendiges Kulturerbe : Turabdin : Wo Die Sprache Jesu Gesprochen Wird (Freunde des Tur Abdin, 1999). Elif Keser Kayaalp, Church Architecture of Late Antique Northern Mesopotamia, Oxford Studies in Byzantium (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2021). Keser Kayaalp, Elif, ed. Syriac Architectural Heritage at Risk in TurʿAbdin. Istanbul: KMKD, 2022. |

| Videos | |

| Website |

| Monument or place to visit | Monastery of Mor Lo’ozor. |

| Style | Remains of Late Antique local masonry structures, later medieval addictions. |

| Type | Fortified monastic complex. |

| Epoch | 6th century – 20th century. |

| State of conservation | Abandoned. “Collapses are observed in the buildings within the courtyard of the completely abandoned monastery. The effects of vandalism are gradually increasing since the entrance of the monastery is not controlled. Numerous illicit excavations are observed within the building. There are also graffiti on the walls, which seem to have been made recently. The large industrial facility to the east of the monastery has a negative impact both on the monastery and the natural landscape of the village” (Altan, Barış. ‘Monastery of Mor Loʿozor’. In Syriac Architectural Heritage at Risk in TurʿAbdin, edited by Elif Keser Kayaalp, 66–69. Istanbul: KMKD, 2022: 67). |

| Degree of legal protection | Designated as “Immovable Cultural Property” by the Diyarbakır Regional Council for Conservation of Cultural Property affiliated to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Included in the World Heritage Tentative List by UNESCO in 2021. |

| Mailing address | Mercimekli, Unnamed Road, 47500 Midyat/Mardin, TR. |

| Coordinates GPS | 37°28'5.56N 41°20'4.37E |

| Property, dependency | |

| Possibility of visits by the general public or only specialists | Accessibile to general public. |

| Conservation needs | “Emergency protective measures should be taken and access to the building should be controlled. The demolishment of the seclusion tower would mean the loss of the last remaining sample in the region” (Altan, 2022: 67). |

| Visiting hours and conditions | |

| Ticket amount | |

| Research work in progress | Cleaning work by Mardin Museum. Documenting and Disseminating the Syriac Intangible Heritage in Mardin’ Project (2018-2019). |

| Accessibility | Easily accessible either by car (3 min) or on foot (15 min) from the nearby village of Mercimekli (Habsenas in Syriac). The village is 15min away by car from the city of Midyat, and 1 hour drive from Mardin. |

| Signaling if it is registered on the route | Not registered yet. |

| Bibliography | Göyünç, Nejat. ‘Ṭūr ‘Abdīn Im 16. Jahrhundert Nach Den Osmanischen Katasterbüchern’. Zeitschriften Der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Deutscher Orientalistentag, Supplement II: XVIII (1972): 142–48. Hans Hollerweger et al., Lebendiges Kulturerbe : Turabdin : Wo Die Sprache Jesu Gesprochen Wird (Freunde des Tur Abdin, 1999), 138-142. Palmer, Andrew. ‘La Montagne Aux LXX Monastères. La Géographie Monastique Du Tur ’Abdin’. In Le Monachisme Syriaque, 169–259. Études Syriaques 7. Paris: Librairie orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 2010: 34. Yaşar, Şükran. ‘Mor Loozor Manastiri’. Mukaddime 2 (2010). Elif Keser Kayaalp, ‘Church Building in the Ṭur ʿAbdin in the First Centuries of the Islamic Rule’, Authority and Control in the Countryside: From Antiquity to Islam in the Mediterranean and Near East (6th-10th Century), 18 October 2018. Keser Kayaalp, Elif. Church Architecture of Late Antique Northern Mesopotamia. Oxford Studies in Byzantium. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2021. Altan, Barış. ‘Monastery of Mor Loʿozor’. In Syriac Architectural Heritage at Risk in TurʿAbdin, edited by Elif Keser Kayaalp, 66–69. Istanbul: KMKD, 2022. |

| Videos | Youtube |

| Information websites | unesco.org wikipedia.org |

| Location | Located in a S-E part of the Anatolian Plateau, characterized by gentle gradients, 5 km north of Midyat (Mardin, Turkey). |