National Architectural and Archaeological Reserve Durostorum

per person

For the protection of the Lower Danube territories against the continuous raids of the Barbarians from the North, after the victory over the Dacians in 106 AD, one of the most capable military units of the Roman Empire was stationed there by order of Emperor Trajan (97 – 117) – Legio XI Claudia. According to the prevailing opinion the name of the town of Durostorum is of a Thraco-Getic or Celtic origin (some translate it as strong fortress), which at least testifies to continuity in toponymy.

The geographer Claudius Ptolemy (AD 2nd c.) was the first to mention Durostorum. Under this name and with different transcriptions, the town is found in the records of ancient authors until the 6th century.

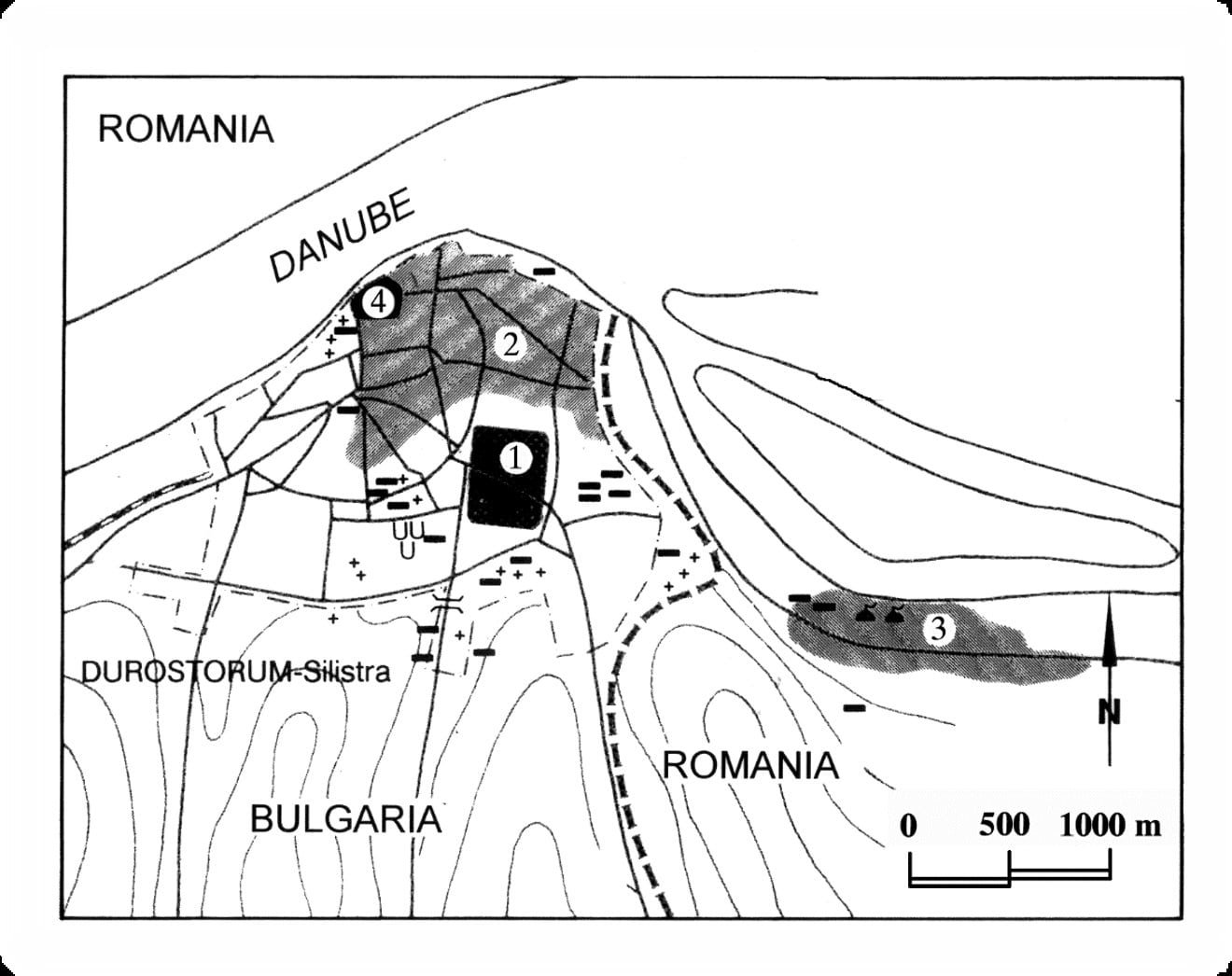

With the arrival of the legion (comprising about 5000 soldiers), the construction of a well-fortified permanent camp immediately began, the imposing ruins of which are located in the southern part of Silistra. According to recent studies, it is rectangular in plan oriented north-south. In the spirit of the classical Roman urban agglomeration, parallel to the camp of the legion, a civilian settlement – vicus arose and developed, located on the eastern outskirts of the camp, mainly on Romanian territory next to the town of Ostrov. This settlement dualism was a common practice in the Rhine-Danube Limes in the 1st – 3rd century. Civilians also moved with the legionnaires – artisans, merchants, immigrants from the territory of the entire Roman Empire and especially from the Eastern provinces, who contributed to the material and cultural prosperity of the town.

Durostorum was also included in the Roman road network. One of the structure-determining highways of the Empire passes through it – the Limes Danube road from Rome via Vindobona (Vienna) to the western Black Sea coast and from Durostorum a main road run south to Marcianopolis and Anchialos on the Black Sea.

During the greatest persecution of Christians in the Empire in 303-304, there were successively martyred St. Dasios, St. Julius, St. Valentininian, St. Pasikrates, St. Nicander, St. Quintilian and St. Callinicus of Dorostol. In 307, St. St. St. Maximus, Dada and Quintilian were executed, and in 362 the last early Christian martyr of Durostorum and Moesia was burned on the banks of the Danube – St. Emilian of Dorostol. In this way, Durostorum became a symbolic center of the Early Christianity along the Lower Danube, which also explains the establishment of an episcopal chair as early as 380, headed by Mercurian – Auxentius, a highly erudite cleric and writer, disciple and follower of Wulfila himself. In 383 he left Durostorum and settled as bishop of Mediolanum (Milan in Italy). The documents of the Ecumenical Councils and other sources mention the names of more bishops of Durostorum.

FORMAL ANALYSIS

The Roman tomb with wall paintings takes a remarkable place from the transition to the Christian Age. It is considered to be the final resting place of a prominent local magistrate. The rich mural decoration (geometric, floral, animal and human figures, hunting scenes, the married couple and their attendants) bears the features of the post-Constantine Age (during the reign of Julian the Apostate or Theodosius I in the last third of the 4th century?) and illustrates the style of a gifted artist who came from the Eastern provinces of the Empire (probably Egypt or Syria). The central panel presents a full-length depiction of the deceased, dressed in the costume of a distinguished Roman general – a magistrate, probably a patrician – military person (commanding from Durostorum the army along the Limes?) holding in his hand an imperial charter – a codicil. Next to him is his noble wife, and on either side attendants bringing vessels and tools for ritual washing, and the elements of the costume of the master – magistrate.

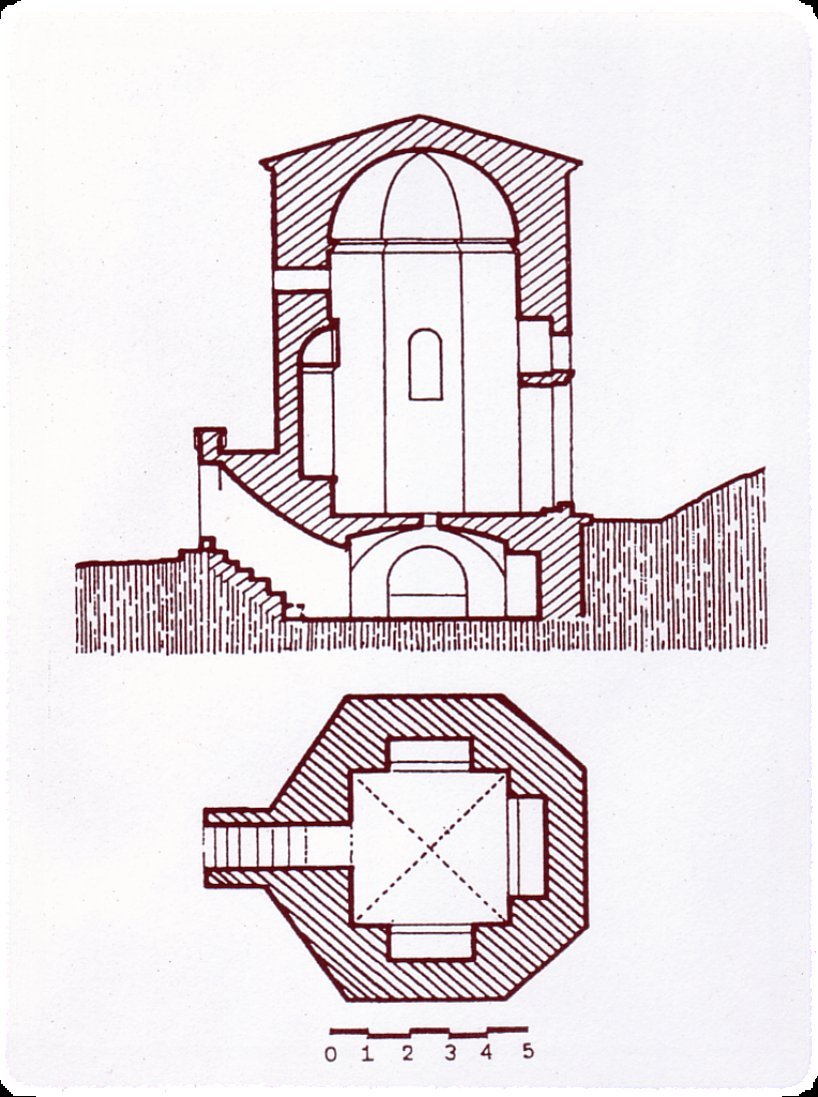

With the confirmation of the town as an episcopal see, changes in the urban planning were ahead. An impressive martyrium-mausoleum with three graves – arcosolia, in which the relics of St. St. St. Maximus, Dada and Quintilian were probably laid, became the accent of the town necropolis.

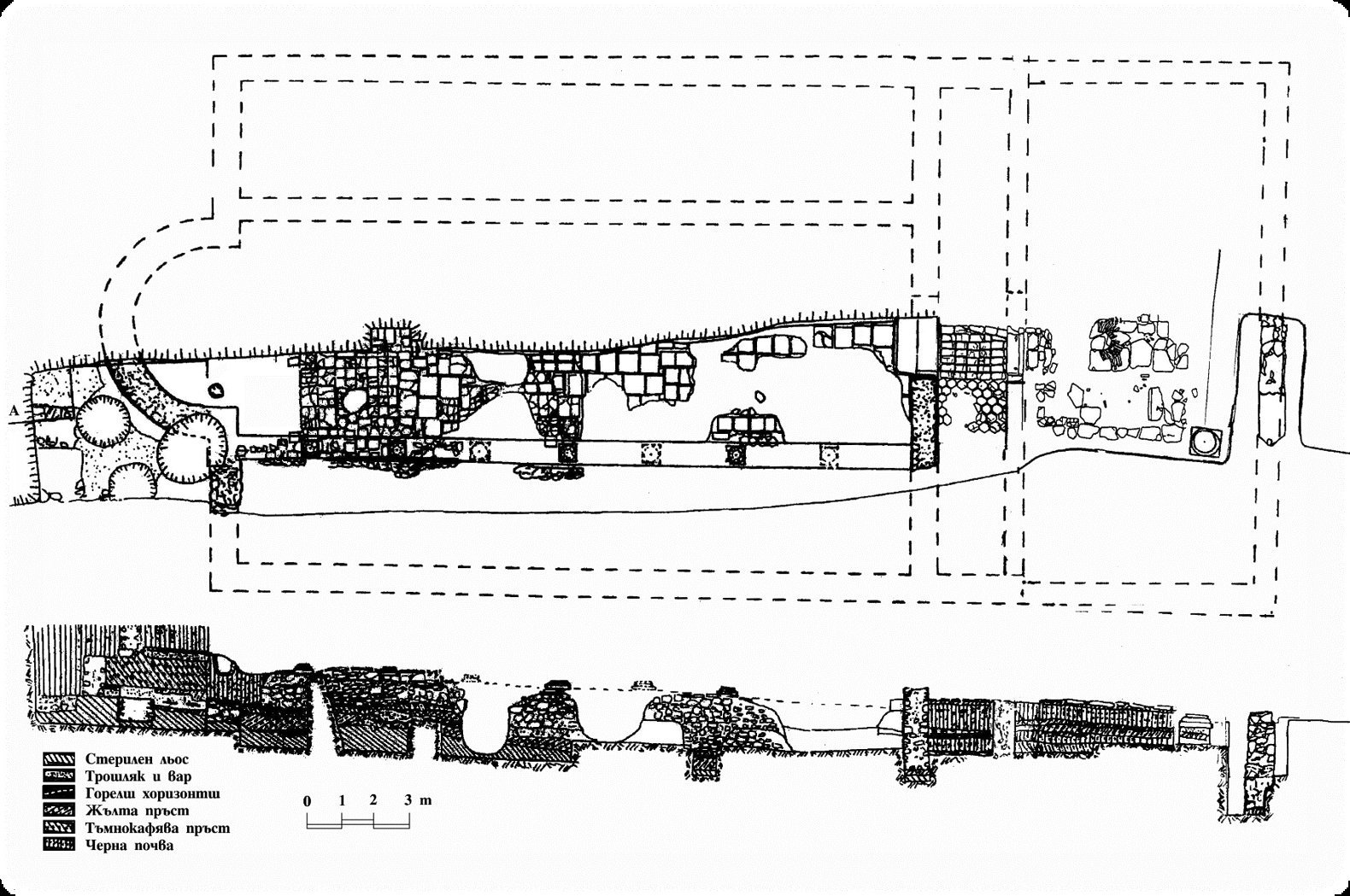

An impressive Early Christian three-nave single-apse basilica with a narthex and an atrium was built approximately in the center of Durostorum. According to the artifacts found, the coins and architectural details, the construction dates back to the late 4th – early 5th century. It was destroyed and burned in the late 6th century. A second, larger basilica was constructed north of it. Three small bells from the 5th-6th century were found in front of it – extremely rare from this era. The pair of basilicas formed in this way was connected to the Episcopal center of Durostorum from the late 4th – 6th centuries. About 70 m to the east, the representative Episcopal residence was erected about the late 4th century over the ruins of the palace of the governors of the province of Moesia from the 2nd-4th centuries. A small private bath for the bishops was revealed west of the residence.

Between the second half of the 4th and the late 7th century, Dobrudzha and Durostorum in particular were subjected to continuous invasions turning into the arena of the clash of the Late Antiquity civilization with the Barbarian world. In 376, hundreds of thousands of Goths entered not far from the town, who after two years ravaged the Eastern provinces of the Empire and burned Durostorum. According to the studies, the town recovered quickly, but changes in the ethnic composition followed with the infiltration of Germanic federates. Apropos, Flavius Aetius, the son of the centurion of the Legio XI Claudia, Gaudentius, born in Durostorum in 390, also was of a mixed ancestry. In practice, for several decades as patrician, consul and commander-in-chief, General Aetius ruled the Western Roman Empire. Thanks to his military genius, in 451 Attila’s Huns were defeated on the Catalaunian plains in France.

During the years of the Great Migration, Durostorum was affected many times, only to be reborn again and again. Despite everything, in 578 the city was captured and destroyed by the Avars and Slavs. According to the coin hoards and other sources, in the late 6th century Dorostol (in the 6th century, the Greek form of the name Durostorum – Dorostol was accepted) was once again rebuilt to continue to exist as the only outpost of Byzantium on the Lower Danube until the arrival of the Bulgars in the late 7th century, led by Khan Asparuh (680 – 701).

As soon as the foundation of the Danube Bulgaria in 681, the Bulgars conquered Durostorum – Dorostol and renamed it Drastar. Unlike other Roman-Byzantine towns in today’s northern Bulgaria, its fortress walls from the 4th-6th centuries were not completely destroyed when the town was conquered by Asparuh. This favored their rapid recovery and the transformation of the town into the main military-strategic, political, spiritual and administrative center of Dobrudzha and the Danube Bulgaria. This process was certainly finalized under Khan Omurtag (814 – 821), who built his Glorious Home on the Danube in Drastar – the Danube residence of the Bulgarian sovereigns.

After the mid 9th century, Drastar became a leading religious center of Bulgaria. After the conversion in 864, and especially in 870, an Episcopal cathedral was established there, headed by Bishop Nicholas, whose name appears within an inscription found at Silistra and on several molybdobullae. As the only surviving early Byzantine episcopal center within the boundaries of the First Bulgarian Kingdom and covered with glory of 12 saints-martyrs in 927, Drastar was chosen as the residence of the first Bulgarian Patriarch Damian.

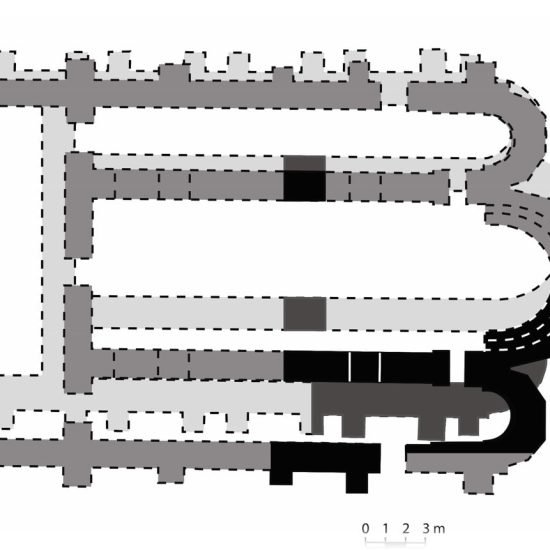

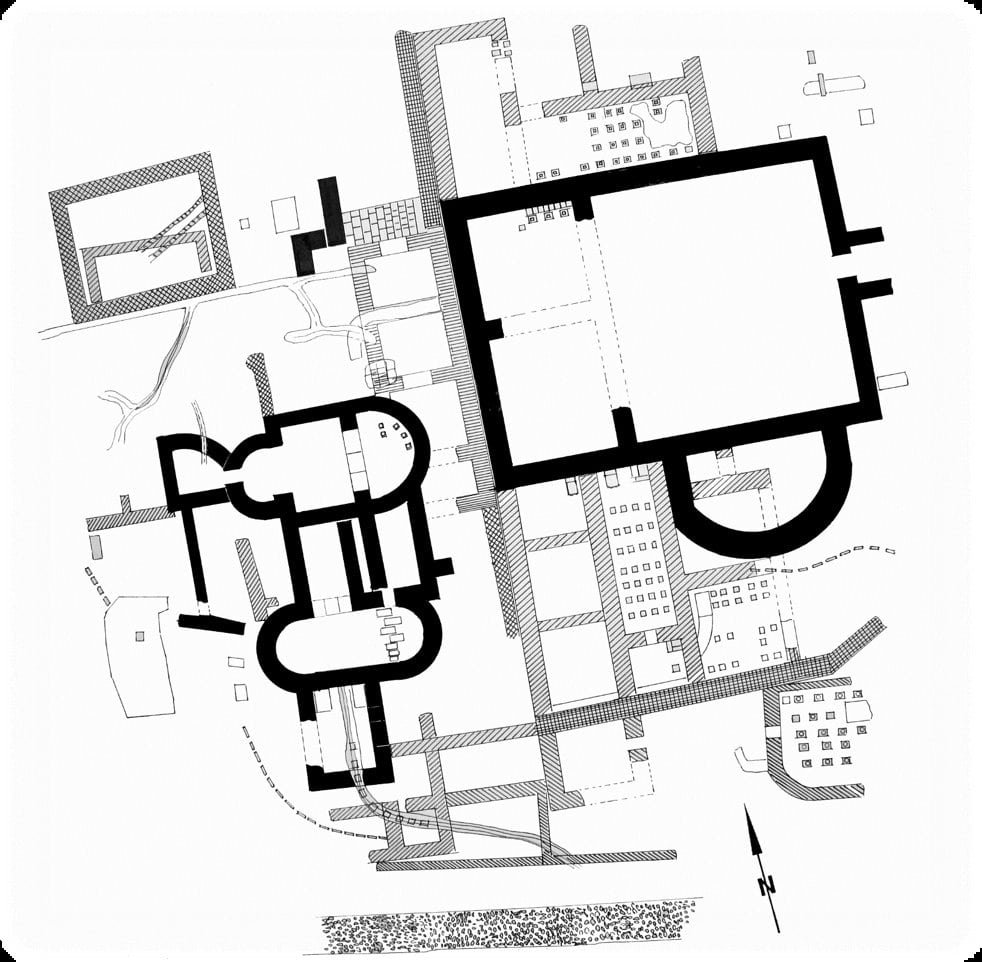

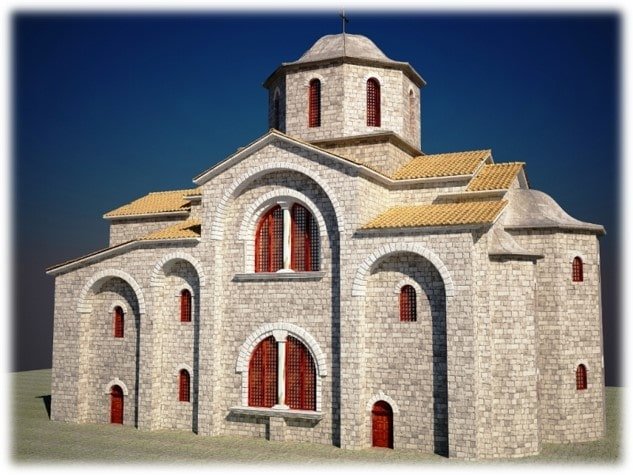

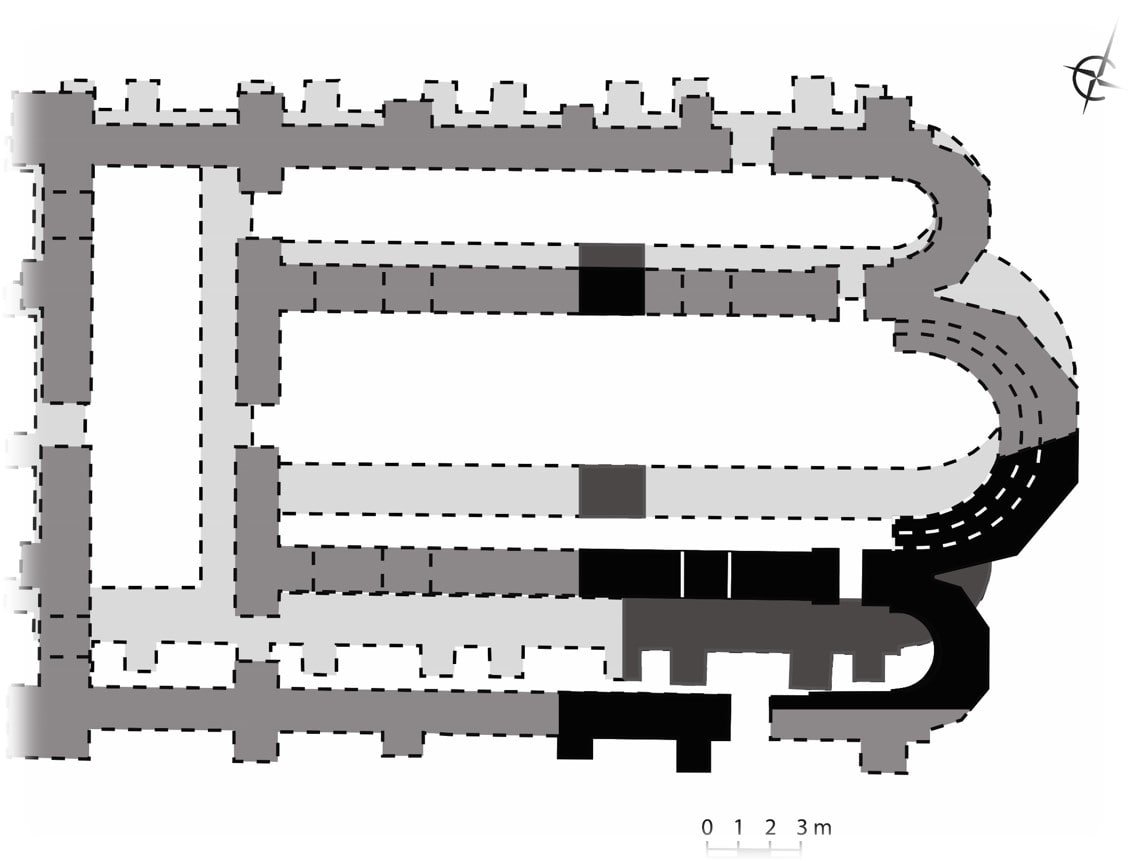

The Cathedral of the Bishops of Drastar in the second half of the 9th century – Church No 4. At the center of the town’s citadel an imposing massive three-nave three-apse basilica has been partially revealed. Next to the northern fortress wall, about 90 m from the Cathedral basilica in the immediate vicinity of the palace of the Bulgarian sovereigns a second palace basilica was built in the mid 9th century (church No 2). It is supposed to have been erected on the spot where, according to the Christian legend, St. Emilian of Dorostol was burned in 362. It is also three-nave and three-apse, massive enough of a quadrae construction. Only 3.90 m to the west of it the Episcopal residence was erected – a massive chain building of 7 rooms. It is archeologically documented that after the early 10th century, the three-nave episcopal cathedral basilica in the center of Drastar was destroyed to the ground, sealed (buried) with two mortar screeds and a new cathedral was raised on its foundation (church No 3). It is a three-nave three-apse cross-domed basilica of the Constantinople type built of quadrae reused from the earlier basilica. The parameters of the Cathedral in Drastar (ca. 33 x 21.60 m) suggest that this is so far the largest archeologically documented cross-domed church of the Constantinople type in the Byzantine cultural circle with the most impressive dome ca. 7.8 m in diameter from the 10th – 11th century. All three apses are pentagonal on semicircular foundations; the central one has a synthronon. In terms of plan and construction, the church has analogues in the Capital town of Preslav from the 10th century, as well as with churches from the early 10th century in Constantinople – the Myrelaion of Romanos Lekapenos and the church of Constantine Lips.

The Palace Patriarchal Church No. 2a is a three-nave three-apse basilica with a narthex. After the beginning of the 10th century, it was rebuilt as a cross-domed basilica, with the addition of a synthronon, a pulpit and a mitatorion in front of the Prothesis. A three-dimensional pre-Romanesque sculptural composition from the 10th century was especially emphasized on the western facade, which recreates Chapter 13 of the Apocalypse.

At the end of the 10th century, Drastar became the arena of one of the most spectacular military conflicts in Medieval European history – the Bulgarian-Russian-Byzantine war of 969-971. After the final conquest of Bulgaria by the Byzantine Emperor Basil II in 1018, Drastar became the center of the huge Paristrion (Danube) Theme, covering all of Northern Bulgaria and Dobrudzha. There the town kept its leading position as a religious centre. As early as the late 10th century, the Rhomaios transformed the Drastar Patriarchate into a bishopric, and in the mid 11th century it was raised to the rank of a metropolis subordinated to the supremacy of the Patriarch of Constantinople.

GEORGI ATANASOV

- DUROSTORUM DRASTAR © TEXT. AND PHOT. GEORGI ATANASOV

- The Roman tomb with wall paintings from the third quarter of the 4th century © PHOT. GEORGI ATANASOV

- Plan of Durostorum 2nd – 4th c. © P. Donevski and G. Atanasov

- Martyrium (of St. St. St. Maximus, Dada and Quintilian) © Photo and plan by P. Donevski

- Early Christian basilica 5 – 6 c. © Plan after G. Atanasov

- Residence of administrative governors from the 2nd – 4th c. and a bishop’s residence on its foundations from the 4th – 6th c. © Plan P. Donevski

- Residence of administrative governors from the 2nd – 4th centuries and a bishop’s residence on its foundations from the 4th – 6th centuries © PHOT. G. Atanasov

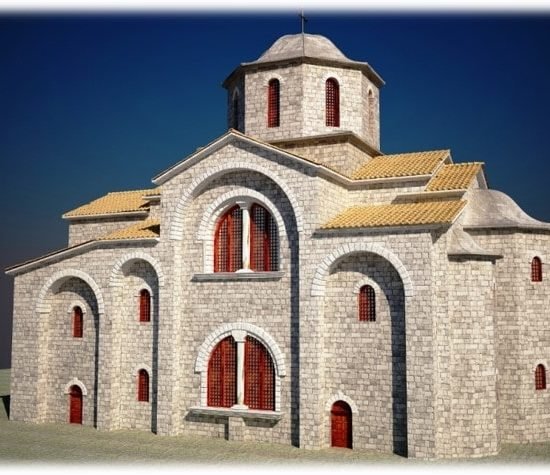

- The Episcopal cathedral basilica from the second half of the 9th c. and the cross-domed Patriarchal church built on its foundations after the beginning of the 10th c. © Reconstruction after G. Atanasov

- The Episcopal cathedral basilica from the second half of the 9th c. and the cross-domed Patriarchal church built on its foundations after the beginning of the 10th c. © Plans after G. Atanasov

- The Palace Episcopal and Patriarchal Church from the second half of the 9th and 10th centuries © Reconstruction G. Atanasov

- The Palace Episcopal and Patriarchal Church from the second half of the 9th and 10th centuries. © PHOT. G. Atanasov

Tour Location

National Architectural and Archaeological Reserve Durostorum

| Other monuments and places to visit | Archaeological Museum - Silistra |

| Natural Heritage | Srebarna Nature Reserve, UNESCO site |

| Historical Recreations | |

| Festivals of Tourist Interest | |

| Fairs | |

| Tourist Office | mysilistra.net |

| Specialized Guides | Yes |

| Guided visits | Yes |

| Accommodations | Plenty of |

| Restaurants | Plenty of |

| Craft | |

| Bibliography | |

| Videos | |

| Website | mysilistra.net visit Silistra |

| Monument or place to visit | National Architectural and Archaeological Reserve Durostorum – Drastar - Silistra |

| Style | Religious and secular architecture |

| Type | Byzantine and Bulgarian architecture |

| Epoch | 4th – 10th century |

| State of conservation | Good |

| Degree of legal protection | Archaeological Museum Silistra |

| Mailing address | museumsilistra@abv.bg |

| Coordinates GPS | 44°06′33″N 27°15′55″E |

| Property, dependency | Monument of culture of national significance, Ministry of Culture of Republic of Bulgaria |

| Possibility of visits by the general public or only specialists | General public visits; the Roman tomb currantly only by specialists |

| Conservation needs | Yes |

| Visiting hours and conditions | The archaeological reserve is located in the open air and is open to the public |

| Ticket amount | Free access |

| Research work in progress | |

| Accessibility | Good |

| Signaling if it is registered on the route | |

| Bibliography | Selected works Г. Атанасов. Християнският Дуросторум - Дръстър. Доростолската епархия през късната античност и средновековието (ІV-ХІV в.). История, археология, култура, изкуство. (The Christian Durostorum – Drastar). Варна - Велико Търново, 2007 . Г. Атанасов. 345 раннохристиянски светци-мъченици от българските земи (І–ІV в.). София, 2011 Г. Атанасов. От епископия към самостойна българска патриаршия в Дръстър. Историята на патриаршеския комплекс. София, 2017, 144 P. Donevski. Zur Topographie von Durostorum. – Germania, 68, 1, 1990, 236-245. G. Atanasov. Le palais des évêques de Durostorum des V-e–VI-e siècles. – Pontica, XXXVII–XXXVIII, 2004–2005, 275–287. ID., Late Antique Tomb in Durostorum - Silistra and its Master. – Pontica, 40, 2007, p. 447-468 St. Angelova, Iv, Buchvarov. Durostorum in Late Antiquity (fourth to seventh centuries). – In: Post-Roman Towns. Trade and Settlements in Europe and Byzantium. Vol. 2. Byzantium, Pliska and Balkans. Berlin-New York, 2007, р. 61-87 |

| Videos | |

| Information websites | museumsilistra@abv.bg |

| Location | Silistra |