Serdica

per person

The birth of Serdica refers to the mid 1st century AD. It is likely that its foundation was connected with the annexation of the Thracian Kingdom of Rhoimetalkes III in 45 AD. The newly formed Roman province was named Thrace and submitted to the rule of a procurator. The archaeological evidence shows that the original settlement was organized on the Roman model – with a proper layout and streets oriented according to the directions of the world. The buildings were of a wood-earth construction. Serdica probably had the function of a military settlement (castellum).

About 112 or after the end of the Second Dacian War, Emperor Trajan gave Serdica and a number of other settlements town status with an adjacent administrative territory. This brought an additional impetus to the development of the town, which became a rich and sustainable Roman provincial center.

The first cataclysm experienced by Serdica was associated with the massive invasion of the tribal union formed by the Costobocae in 170. The town was set on fire, as evidenced by the massive burnt layer registered everywhere. Immediately after the invasion, in the period between 176-180 (during the reign of Emperors Marcus Aurelius and Commodus), the first fortress wall was erected, and the initiative is reflected in dedicatory inscriptions set up above the city gates (two of them found so far). The town has been rebuilt and active construction was taking place within the boundaries of the fortified area.

The Barbarian invasions and the state crisis in the 3rd century did not affect the development of Serdica. Although during the Gothic unrest some of the suburban mansions were damaged, the fortress wall stood and no destruction is reported in the town. In 271/272, Emperor Aurelian carried out a new territorial layout of the southern Danubian provinces. Serdica was chosen as the Capital of the newly formed Dacia (Aurelian Dacia). In the subsequent division of the province, the town became the Capital of Dacia Mediterranea. This administrative format remained unchanged until the end of the Late Antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages.

The reign of Emperor Constantine the Great gave a new drive to town prosperity. The emperor declared his affection for Serdica, and historical records show that he and members of the imperial family visited the town many times. The archaeological investigations testify to a new intensive construction that covers almost all neighborhoods of Serdica. After the relative calm for much of the 4th century, the Balkan provinces of the Eastern Roman Empire once again became the arena of internal and external conflicts. One of them has a direct impact on Serdica. Around the mid 5th century, a significant number of out-of-town economic and residential complexes, monasteries as well as private and public buildings ended their existence in fire. The destructions are associated with the Hun invasion of 443 or 447.

The time of Emperors Anastasius and Justinian I was the last period of relative peace. New construction projects were carried out and the fortress walls significantly strengthened.

In the late 6th century, the Serdica probably fell victim to a natural disaster. Almost everywhere, massive destructions are registered indicating the fierce power of an earthquake. This time, Serdica failed to recover. Although some buildings and streets continued to function, a significant part of the street network remained in ruins. Almost no constructions are registered from that time.

Probably a Barbarian invasion in the second decade of the 7th century was the reason for the abrupt cessation of coin circulation, and of life in the town in general. Most researchers agree on the idea that the Serdica was directly affected during one of the Avaro-Slavic invasions, probably in 614/615.

In 809 Khan Krum captured Serdica and a bit later it was annexed to the Bulgarian Kingdom.

The first half of the 4th century was associated with a global change for the Roman Empire – the adoption of Christianity. The noteworthy reflection for Serdica is expressed in its formation as an Episcopal center. Its significance is contained in the selection of the town as the venue for the Church Council in 343. The council was conceived as ecumenical. The cause was the condemnation of Arius Presbyter of Alexandria (256 – 336) who had renounced the divine nature of the Son. During the council, the followers of Arius left the sessions and headed to Philippopolis, where they held a counter-council. In any case, the earliest contradictions between the Eastern and Western fathers of the Church also emerged at this Council, later developing to reach the Schism in 1054. Among the important Council decisions was the confirmation of the Serdician canons, which makes it the second one of the 17 canon-making councils of the Church. Despite the numerous works dedicated to Serdica Council, there are still unclear details, one of which is the exact scene.

FORMAL ANALYSIS

Another aspect associated with the new religion is the active construction of Christian temples. Some of them were reconstructed older buildings, and others – newly built. By the opening of the Middle Ages, in the fortified territory of Serdica and in its immediate vicinity, more than 15 buildings, which can be connected to early Christianity, were fully or partially uncovered, as some of them are still active today (Saint Sophia Church and Saint George Rotunda).

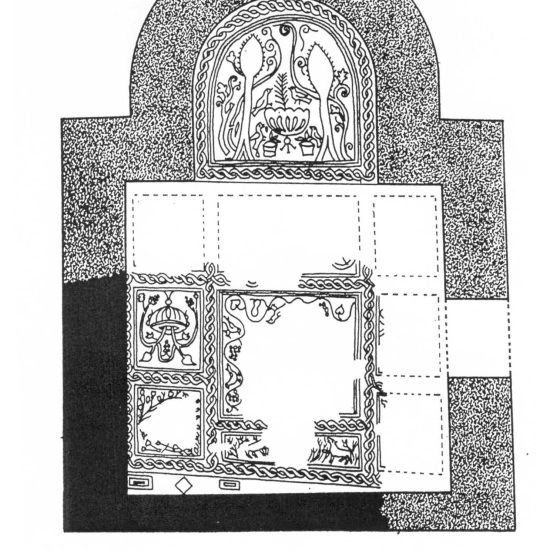

Saint Sophia still attracts great scholarly and public interest. For more than a century, the attention to the church continues to be strong, and to this day there are a number of unsolved questions related to its origin, the stages of reconstruction, and the functions it performed. According to the data collected from the long-term archaeological research, it can be assumed that the original building appeared in the early 4th century. It was beautifully decorated with mosaics in the altar and nave, preserved to this day. The mosaic in the altar represents one of the earliest Christian representations of the Paradise – the Garden of Eden (today on display in the Sofia National Archaeological Museum). A period of several reconstructions of the Christian church followed. Dedicated to Christ Sophos, the Holy Wisdom, it underwent continuous development, with each successive building being larger and more representative.

Today, an archaeological museum is located in the basement of St. Sophia, which contains the architectural remains from the reconstruction of the church, as well as different types of tombs. The naos of the initial church from the 4th century is covered with the original mosaic.

The red-brick St. George Rotunda is an active church. The building belonged to a large ancient complex from the AD 2nd century. In the 4th century it was transformed into a church. It is a central domed structure circular in plan on a square base with four semi-circular niches in the corners. The dome rests on a drum with eight cylindrical windows. Five layers of frescoes, preserved in fragments, were painted sequentially. The earliest one is from the 6th century and contains floral patterns. In the late 9th or early 10th c., a new layer composed of 2 friezes was laid. Fragments of 6 flying angels, as well as the head of one of them, have survived from the upper frieze. The lower frieze contained the images of prophets, today seriously damaged. The third layer is Byzantine from the late 11th – early 12th c. and is filled with saints, prophets and scenes of the Ascension, Assumption, etc. From the fourth layer, applied in the 14th century, a central image of Christ Pantocrator has been preserved. The last mural layer is ornamental from the late 16th century, when the rotunda was for a time converted into a mosque.

Inextricably linked with Christianity was the change of the burial rite. There are two urban necropolises registered to date – the Eastern one, functioning in the 2nd-6th century, and the Western one, organized in the 4th century. The Eastern necropolis is dominating in terms of area and number of burial structures. After the Christianization of the town, the Saint Sophia Church became an attraction center, with the highest density of burials around and in it. Those associated with Christian burials are mainly simple burial pits and vaulted and flat tombs. Many tombs have interior decoration of mosaic floors (in single tombs) and wall paintings. In the wall decoration, the most popular pattern was the cross, painted in various variations. Apart from it, other Christian symbols are also registered – flowers, Chrisms, clusters, garlands and birds. Two tombs are of a particular interest – with images of archangels (Gurko Street) and with an inscription reading: Honorius, Servant of God (Moskovska Street, in front of St. Sophia Church and opened to public).

Also of interest is the only monastery discovered so far in Serdica, located in Lozenets residential area. An early Christian church was built on the site about the third decade of the 4th century. It functioned until the early 5th century, when a massive three-nave basilica was erected over it. In the middle of the century, a fence was built around it, which turned the basilica and the space around it into a fortified ecclesiastic complex. It functioned until the early 6th century, when a pottery workshop was formed on the site.

Until the end of the Late Antiquity, Serdica continued to be an important Episcopal center. The names of a considerable number of bishops are already known. In the late 6th century, an epigraphic inscription shows that even some of the functions of the town administration were performed by the bishop of Serdica (Archbishop Leontius supervised the repairs of the urban water supply).

The Christian heritage of Serdica has its reflection throughout the centuries. It is no coincidence that dozens of monasteries, known today as the Little Sophia Holy Mountain, were founded around the town area during the Middle Ages. Today they are included in pilgrimage routes. Among the numerous temples is the world-famous Boyana Church (wall paintings from 1259), which is included in the list of world cultural heritage under the protection of UNESCO (1979).

ALEXANDER STANEV AND KATYA MELAMED

- SERDICA © PHOTS. KRASSIMIR GEORGIEV

- St. Sophia. General plan of all the reconstructions

- St. Sophia. 4th c. with mosaics. Drawing

- Mosaic of the Paradise. St. Sophia. 4th c. © PHOT. KRASSIMIR GEORGIEV

- St. Sophia silver reliquary with gold-plated Christ monogram. 4th c. © PHOT. KRASSIMIR GEORGIEV

- St. Sophia silver religuary back side. 4th c. © PHOTS. KRASSIMIR GEORGIEV

- Tomb wall painting. Eastern necropolis, Serdica. Drawing (2) © PHOT. KRASSIMIR GEORGIEV

- Tomb wall painting. Eastern necropolis, Serdica. Drawing © PHOT. KRASSIMIR GEORGIEV

- The New Hero. Obzor, second half of 6th c. NAIM-BAS © PHOTS. KRASSIMIR GEORGIEV

Información de la localidad

Serdica

| Other monuments and places to visit | Sofia Regional History Museum; National History Museum |

| Natural Heritage | |

| Historical Recreations | |

| Festivals of Tourist Interest | |

| Fairs | |

| Tourist Office | visitsofia.bg |

| Specialized Guides | Sofia Free tour; tourist companies |

| Guided visits | Yes, in all museums mentioned |

| Accommodations | Plenty of |

| Restaurants | Plenty of |

| Craft | Yes |

| Bibliography | |

| Videos | |

| Website |

| Monument or place to visit | St. Sophia Church with the Underground Museum, St. George Rotunda, Tomb of Honorius, National Archaeological Museum |

| Style | Still active Late Antiquity churches |

| Type | Monastic architectureEarly Christian Church architecture Artefacts found during archaeological research |

| Epoch | 4th – 6th centuries and later |

| State of conservation | Excelent condition |

| Degree of legal protection | Bulgarian Orthodox Church St. Sophia Archaeological Level and Crypt – Regional Historical Museum Sofia National Archaeological Museum – NAIM – Bulgarian Academy of Sciences |

| Mailing address | polina.stoyanova@sofiahistorymuseum.bg naim@naim.bg |

| Coordinates GPS | 42°41′50″N 23°19′42″E |

| Property, dependency | Bulgarian Orthodox Church |

| Possibility of visits by the general public or only specialists | St. Sophia Church and St. George Rotunda are active churches with regular services, opened to general public |

| Conservation needs | Yes |

| Visiting hours and conditions | St. Sophia Archaeological Level and Crypt May - October: Monday to Sunday 10:00 a.m. – 05:30 p.m. November - April: Tuesday to Sunday 10:00 a.m. - 05:30 p.m. National Archaeological Museum May – October: Monday to Sunday 10 a.m. – 6 p.m. November – April: Tuesday to Sunday 10 a.m. – 5 p.m. |

| Ticket amount | St. Sophia Archaeological Level – 6 BGN National Archaeological Museum – 10 BGN Various discounts depending on the number of visitors, age, etc. |

| Research work in progress | |

| Accessibility | Good |

| Signaling if it is registered on the route | |

| Bibliography | Selected works Бояджиев С. Сердика (Serdica). Градоустройство, крепостно строителство, обществени, частни, култови и гробнични сгради през ІІ-ІV в. - In: Р. Иванов (edit.) Римски и ранновизантийски градове в България, І. София, 2002, 125-180. Динчев В. Римските вили в днешната българска територия. Sofia, 1997. Мешеков Ю. Мешеков. Последни археологически разкрития в и около базиликата „Св. София”, източен некропол на Сердика. - In: Д. Ботева-Боянова at all. Общество, царе, богове. Сборник в памет на проф. Маргарита Тачева. София, 2018, 301-318. Станев А. Влиянието на варварските нашествия през ІV и V век върху историческата стратиграфия на Света София. – In: Сердика – Средец – София“. 2018. V. 7. Proceedings of the Saint Sophia at the Transition between Paganism and Christianity International Scientific Conference. Sofia, March 11th – 13th 2014, 481-493. Шалганов К. Археологически проучвания под базиликата “Света София” в София през 1991-2002 г. – In: HEROS HEPHAISTOS. Studia in honorem Liubae Ognenova-Marinova. V. Tarnovo, 2005, 469-480. Шалганов 2011: Шалганов, К. Археологическите паметници в София. Пътеводител. София. Daskalov-Goryanova. Early Christian architectural complex in Sofia (Bulgaria). Niš & Byzantium. VII. 2009, 151-162. N.B. All the works are accompanied by summaries in English or French. |

| Videos | |

| Information websites | |

| Location | In central sector of Sofia |