Monastery of St. Chrysogonus

per person

DESCRIPTION AND FORMAL ANALYSIS

The monastery of St. Crysogonus (Krševan) emerged next to the church of St. Chryosgonus, which was built to honour the earthly remains of this martyr, which according to legend were brought to Zadar from the town next to Aquileia as early as 649. The first mention of this monastery is found in the will of the Zadar prior Andrija from 918. The abbot mentioned as a witness in the will was Adalbert from St. Chryosgonus Abbey. According to available historical sources, during the 10th century, the monastery was closed down. It came to life again at the end of 986 when the Zadar prior Majo, in agreement with the Zadar nobles and other citizens, allowed the building of a new monastery, next to the church of St. Chryosgonus, on the site of the old one in order to organize the monastery life according to the rule of St. Benedict. The arrangement of the monastery was entrusted to abbot Madi, originally from Zadar, who came to Zadar from Montecassino. Several Croatian rulers and dignitaries endowed the monastery with properties, among them was king Petar Krešimir IV. He confirmed many properties in Diklo to the monastery, and in 1069 he donated the entire island of Maun.

Until the end of the 14th century, while Zadar had city autonomy, the monastery was constantly growing stronger and enjoyed a great reputation in the entire region. In the political turmoil between the Republic of Venice and the Hungarian-Croatian Kingdom, the monks together with the abbot took the side of the people of Zadar and thus opted for the Hungarian-Croatian King Ludovic.

With the occupation of Dalmatia by the Republic of Venice in 1409, the monks of St. Krševan fell into their disfavour. The Venetians tried in every way to reduce their political influence and economic power. Despite their efforts, the monastery still enjoyed a great reputation among the people. Pope Nicholas V decided on 30 December 1447 that the monastery of St. Chryosgonus be turned into a commendam.

All this led to its weakening and neglect, the number of monks was very low, so that at the end of the 18th century there were only two to three monks in the monastery, mostly Italians. At the end of 1619, it was joined to the Montecassino Congregation of St. Justin in Padua. Through the efforts of Zadar archbishop Vicko Zmajević, Pope Benedict XIII in 1729 assigned the properties and income of the monastery of St. Chryosgonus to the Illyrian seminary, which was founded by archbishop Zmajević for the education of the Croatian clergy. With the arrival of the French authorities in 1807, the monastery was entirely closed.

Throughout its rich history, a rich scriptorium operated in the monastery. The activity of the scriptorium can be traced from 986, when the monastery was renovated and reorganized, until the end of the 15th century.

IVAN BODROZIC AND IVAN BALTA

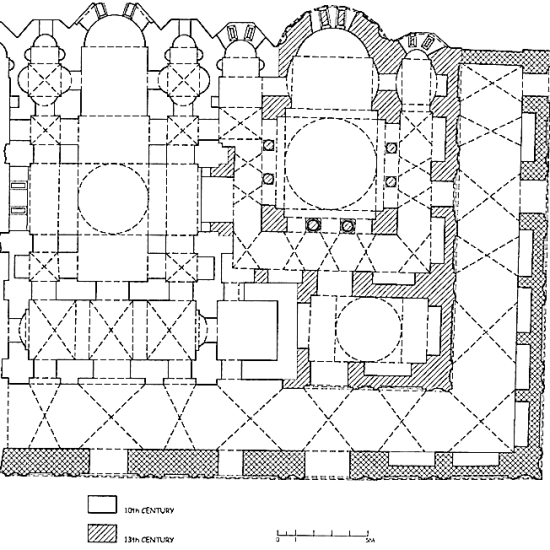

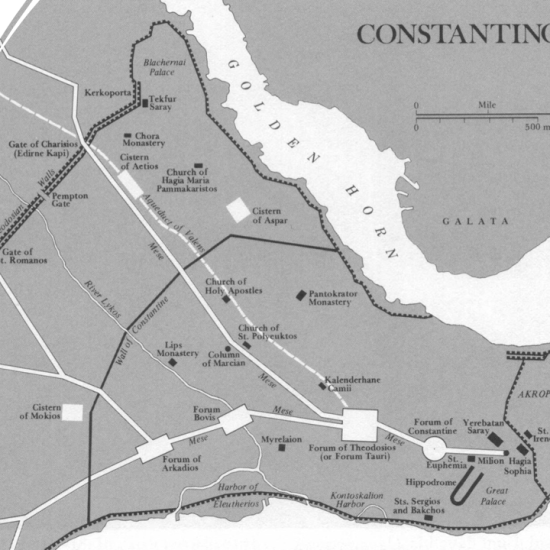

- MONASTERY OF St. CHRYSOGONUS © PLAN. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE MONASTERY AND THE CHURCH OF ST. CHRYSOGONUSI. BAVČEVIĆ, 1986

- MONASTERY OF St. CHRYSOGONUS © PHOT. https://zadar.travel/hr/atrakcije/atrakcije/crkva-svetog-kr%C5%A1evana

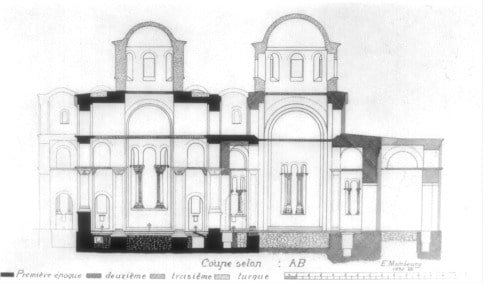

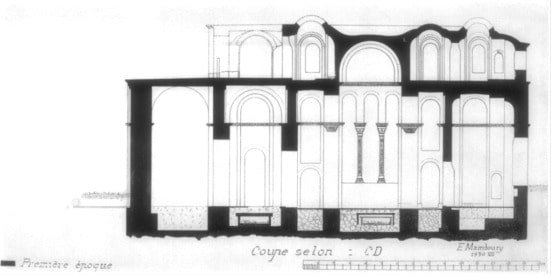

- PLAN ON THE FRONT FACADE AND THE SIDE FACADE OF THE MONASTERY CHURCH OF ST. CHRYSOGONUS © PLAN. I. PETRICIOLI, 1986

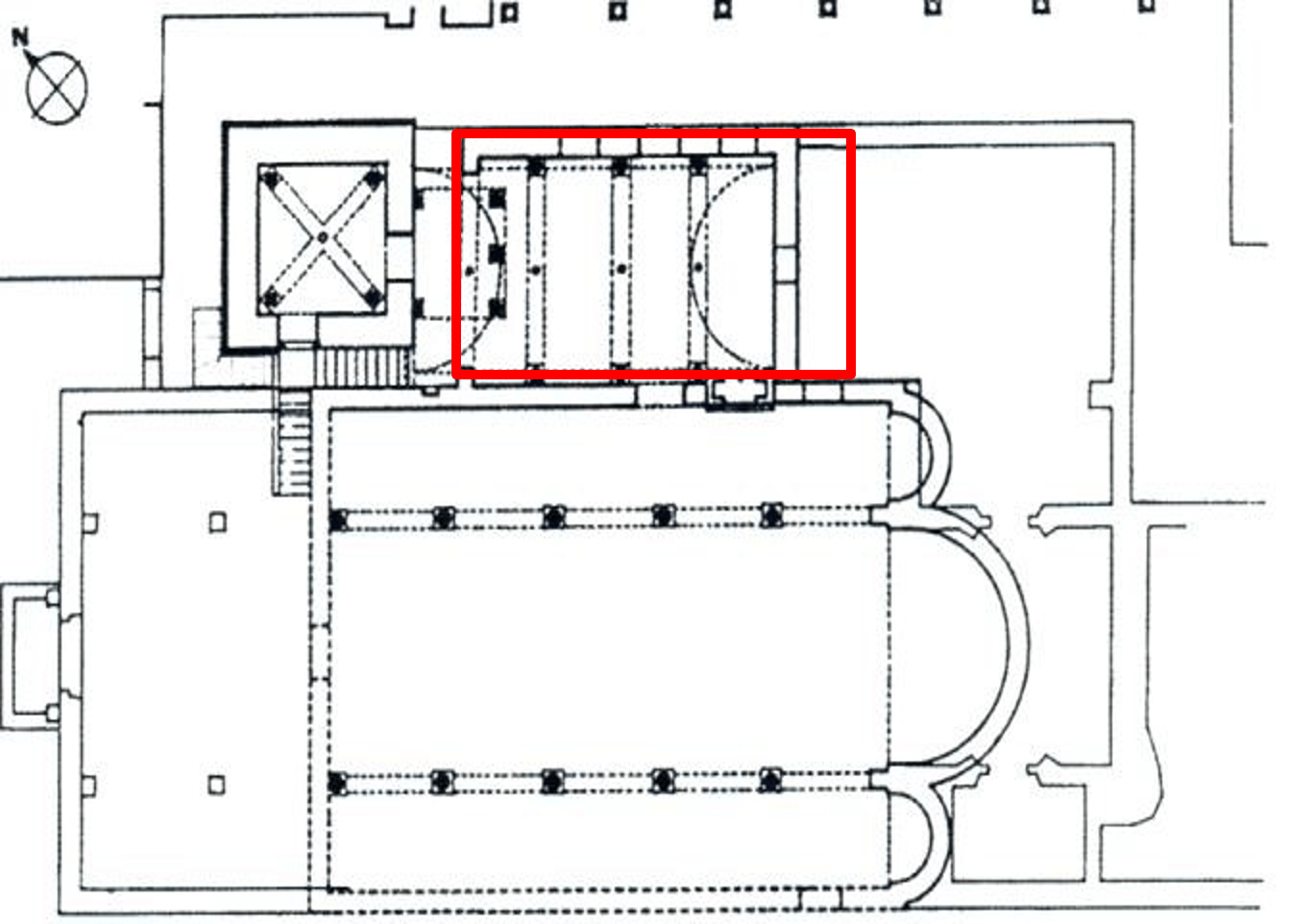

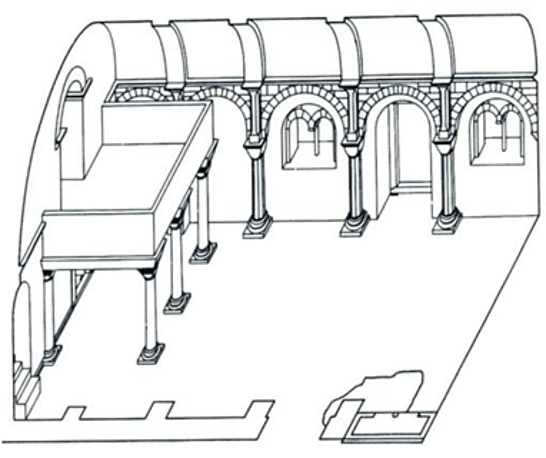

- CHAPTER HOUSE OF THE MONASTERY OF ST. MARY © PLAN. A. MARINKOVIĆ, 2005

- CHAPTER HOUSE OF THE MONASTERY OF ST. MARY © PLAN. A. MARINKOVIĆ, 2005

- CHURCH OF ST. CHRYSOGONUS, INTERIOR © PHOT. I. JOSIPOVIć, IN I. TOMAS, 2017

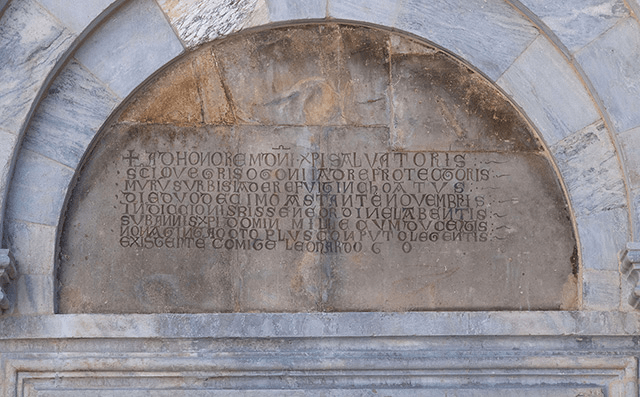

- INSCRIPTION FROM THE FRONT FAÇADE OF THE CHURCH © PHOT. https://www.hrz.hr/index.php/aktualno/novosti-i-obavijesti/3938-zadar-crkva-sv-krsevana

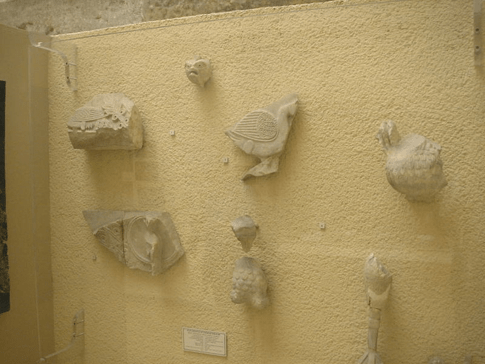

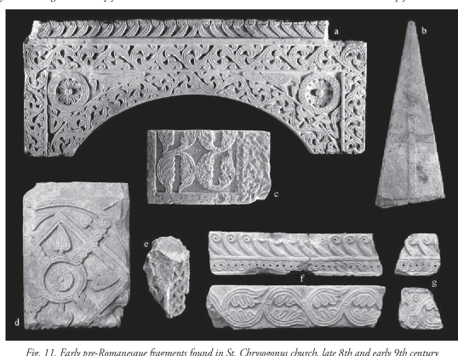

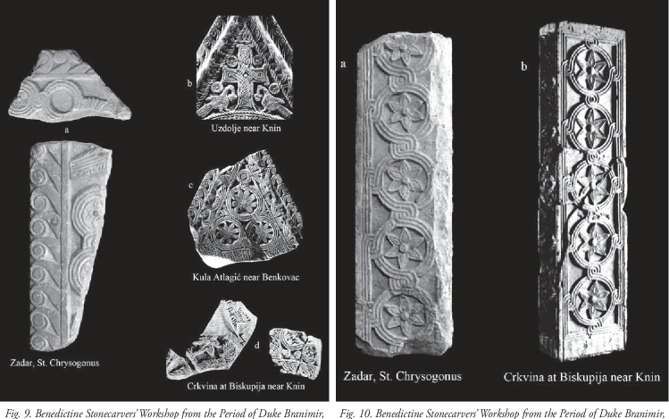

- HIGH MEDIEVAL DECORATIVE REMAINS, ZADAR MUSEUM © PHOT. Ivan Josipović, Ivana Tomas, 2016

- HIGH MEDIEVAL DECORATIVE REMAINS, ZADAR MUSEUM © PHOT. Ivan Josipović, Ivana Tomas, 2016

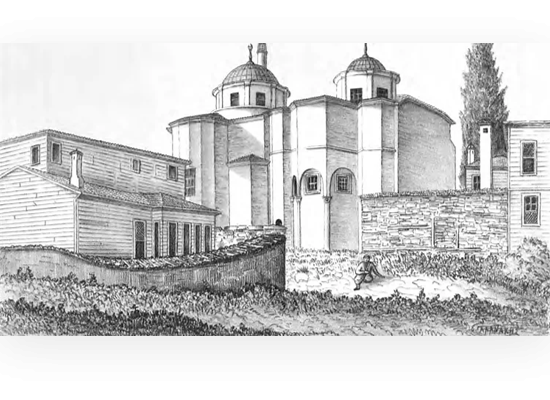

- RECONSTRUCTION OF THE CHURCH AND BENEDICTINE ABBEY OF ST. Krševan (CHRYSOGONUS) IN ZADAR, Iveković, 1931 © PHOT. https://www.croatianhistory.net/etf/art.html

Información de la localidad

Monastery of St. Chrysogonus

| Other monuments and places to visit | Church and Monastery of Saint Mary Church of Saint Donatus The Cathedral Church of Saint Simeon |

| Natural Heritage | |

| Historical Recreations | |

| Festivals of Tourist Interest | |

| Fairs | |

| Tourist Office | Yes |

| Specialized Guides | Yes |

| Guided visits | Yes |

| Accommodations | Yes |

| Restaurants | Yes |

| Craft | |

| Bibliography | |

| Videos | |

| Website | wikipedia.org benediktinke-zadar.com zadar.travel |

| Monument or place to visit | Monastery of St Chrysogonus |

| Style | Romanic art Interior: Romanesque-Byzantine frescoes |

| Type | |

| Epoch | Xth century |

| State of conservation | Good |

| Degree of legal protection | |

| Mailing address | |

| Coordinates GPS | 44°06'57.9N 15°13'34.7E |

| Property, dependency | |

| Possibility of visits by the general public or only specialists | General visits |

| Conservation needs | |

| Visiting hours and conditions | |

| Ticket amount | |

| Research work in progress | |

| Accessibility | |

| Signaling if it is registered on the route | Yes |

| Bibliography | Josipović, I. - Tomas, I., 2017: “The Abbey of St. Chrysogonus in Zadar – between Early Christian sculpture and the Romanesque architecture”, Hortus Artium Medievalium Vol. 23, 299-308. |

| Videos | zadar.travel |

| Information websites | zadar.travel wikipedia.org |

| Location | Zadar |