Lips Monastery

per person

The Monastery of Lips was a complex of two connecting churches. The first one of which (North church) was restored by the patrician Konstantinos Lips from a sixth-century church (Macridy, Theodore. ‘The Monastery of Lips and the Burials of the Palaeologi’. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 18. 1964: 258) and consecrated to the Theotokos (Mother of God) in June 907. Nothing is known about the monastery or the church until the very late thirteenth century, when Theodora Palaiologina, widow of Michael VIII, restored and expanded the monastery, adding the second religious building (South church), dedicated to the Prodromos (St. John the Forerunner) and intended as mausoleum for herself and the family of Palaeologi.

Almost contemporaneously, a long exonarthex was added to both churches. After 1453, said Spingou (2012, 18) the complex remained in Christian hands until after 1460, when it was turned into a mescid (small mosque without a pulpit) although without any critical alterations. In 1633, the complex was seriously affected by a fire which destroyed half of the city. Three years later, it became a regular mosque. Radical changes to the structure occurred around this time” (Spingou, Foteini. ‘Revisiting Lips Monastery. The Inscription at the Theotokos Church Once Again.’ The Byzantinist, no. 8–9. 2012: 16). “Unfortunately, the modern visitor sees little of the original church. The lavish decoration is missing. The impressive findings of the archaeological surveys are now in the archaeological museum of Istanbul. Most importantly, except for a part of the East façade and a tiny fragment of the North façade, the original façades have been fundamentally altered. The South façade was adjusted in order to fit the Palaiologina’s plan, the West was changed dramatically when the exonarthex was build, and chapel B, at the North, is now in ruins.

At the end of the 15th century, the south church was converted into a small mosque. After a fire in 1633, it was restored while the north church became a tekke (a dervish lodge). It was during this time that the domes were renovated, columns in the north church replaced by piers whereas the mosaics were removed. In 1782, there was another fire which caused damages; the building was restored again in 1847/8. During this restoration further changes took place: in the south church piers replaced the columns, whereas the parapets of the narthex were removed too. In 1918 a third fire took place which led to the abandonment of the building. In 1929 were conducted excavations and 22 sarcophagi were discovered. The Byzantine Institute of America restored the monastery in the 1950s and 1960s. From the monastery survive only the churches and is again a mosque. Extensive restoration and rehabilitation is undergoing since 2000.

FORMAL ANALYSIS

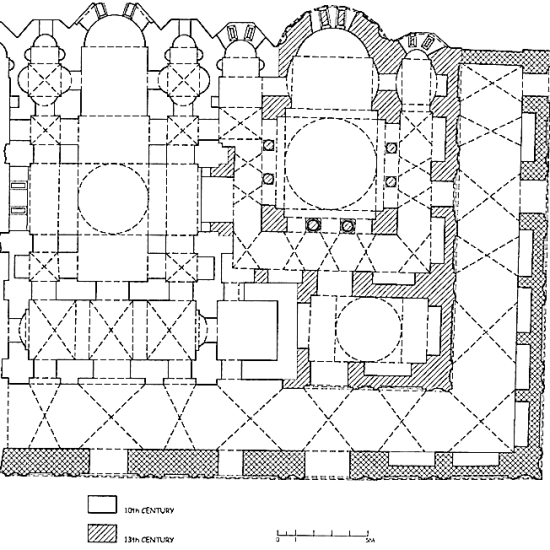

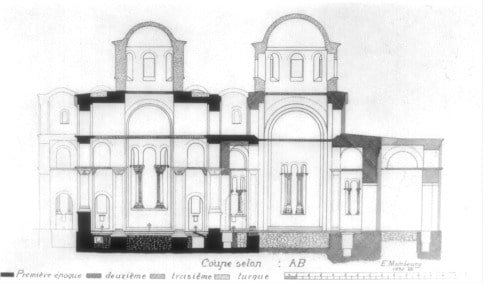

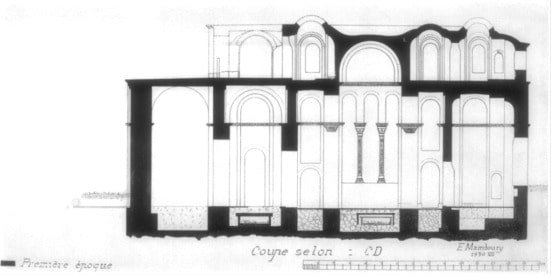

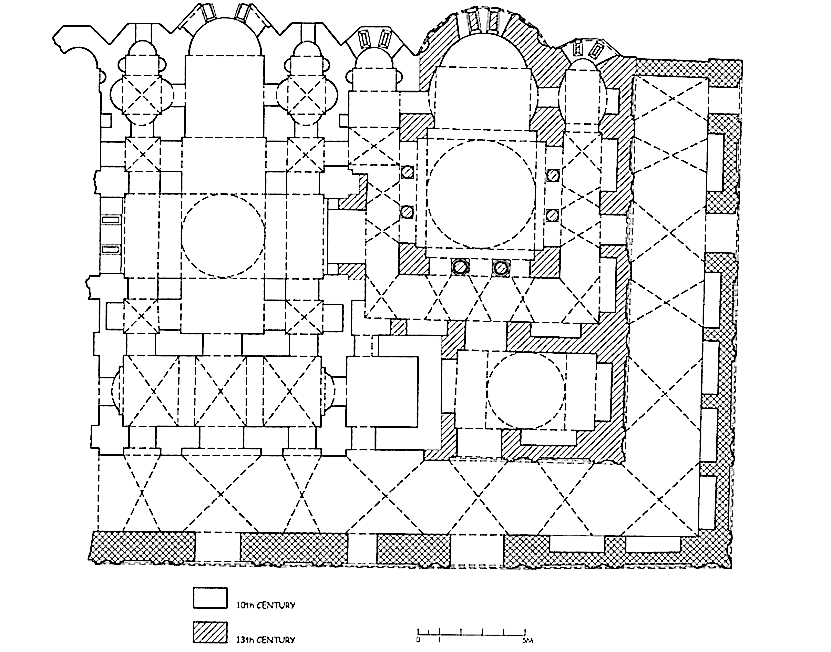

The katholikon of the monastery consists of two churches, the northern and the southern one – respectively five- and three-aisled – being cross-in-square structures. The Church of the Mother of God, the more ancient of the two, is considered by Theodore Macridy “a rare and splendid example of Byzantine architecture”. “The length of the nave is 14.50m., its width 9.50m. To the latter figure should be added the width of the two outside aisles, of which the northern one has been destroyed, although its foundations were found in the course of archaeological excavations. The narthex, which has three doors corresponding to those of the nave, is 9.50m. long and 3.20m. wide. On either end of it was a square, tower-like structure communicating with the narthex. These structures had doors facing east and west, the former leading into the interior of the church, the latter leading out. Within these structures (the northern one is no longer in existence) were wooden staircases leading up to the roof. The interior height of the church from the floor to the base of the dome is 11.50 m” (Macridy, 1964: 258).

The stonework of the walls is the same below the tenth-century level as it is up to a height of 60 cm. above that level. Next comes a band consisting of five courses of brick, and above that is another band of stone. This system of construction, namely alternating bands of brick and stone, was introduced before the sixth century and continued to be used in the succeeding period. In any case, the lower part of the walls up to a height of 2 m. belongs to a building older than the tenth century. During his studies Macridy was able to ascertain that the architect of Konstantinos Lips retained the plan of the previous church and a large part of its structure which he adapter in some respect. However, in order to differentiate the original parts of the building from those of the tenth century further studies have to be done (Macridy, 1964: 261).

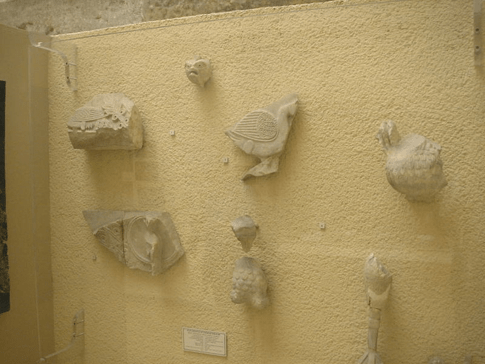

Furthermore, it appears that the tenth-century architect was not content to reuse the walls of the older church, but did the same also with its carved interior ornaments (Macridy, 1964: 261). Four capitals, characteristic of the sixth century, surmount the pilasters corresponding to the four free-standing columns. According to Macridy, the architect of the tenth century took this decorative material from the sixth-century church. (Macridy, 1964: 259). Under the Turkish floor of the northern church, many beautiful carved fragments of the sixth century which must have come from the same church (among these: four draped torsos executed in a classicizing technique, and two heads). Several fragments of eagles carved in high relief. Fragment of the archivolt with representations of the apostles, originally from a rectangular tympanum (Macridy, 1964: 262).

Of particular interest is the roof of the church upon which were built four independent chapels in the four corners formed by the cruciform space in the center. The floor of the chapels and of the connecting passages is supported by the vaulting of the lateral aisles. The intervening spaces in the roof were filled with inverted water-jars, so as to decrease its weight. Originally, the roof was reached by means of wooden staircases placed in the projecting structures on either side of the narthex. Today it can be reached only through the base of the minaret (Macridy, 1964: 260).

The church of St. John the Forerunner has different system of construction from the austere symmetry of the northern church: for example, the main entrance is noticeably off axis. Everything shows great haste in the completion of the building which was intended as the last dwelling-place of Theodora and members of her family. The parts of the building erected by Theodora are shown cross-hatched on the ground plan. The narthex includes on the left the staircase well of the north church. In its floor may be seen the bases of four columns which supported a ciborium. The right-hand part of the narthex was used as a place of burial; it is covered with a dome which originally had a tall drum lit by eight windows. The present low dome is Turkish. The carved marble cornice at the base of this dome is fairly well preserved (Macridy, 1964: 265).

The north church is small in size (13 m x 9,5m) and has a rather unusual plan (cross-in-square in a pentagonal form). The masonry follows the typical byzantine type of the 10th century, where stripes of brick followed alternatively by stripes of stone blocks. The most unique feature of the north church is that it has four chapels in all four sides of the dome.

The north church has three apses, the middle of which is polygonal. It has also two long chapels with a low apse. The original decoration of the church included coloured tiles, mosaics and marble panels of which only few spolia have survived (see also gallery of images).

The south church was added in the late Byzantine period and has a square form. It includes a dome, two deambulatoria, an esonarthex and a chapel (added later). The spatial additions around the dome played the role of a funeral space for the deceased members of the founder’s family. This testify also the sarcophagi found during excavations in the building.

The masonry is composed of rows of alternated courses of bricks and stone while the bricks form various decorative patterns.

- LIPS MONASTERY Reconstructed ground plan by E. Mamboury https://www.thebyzantinelegacy.com/lips

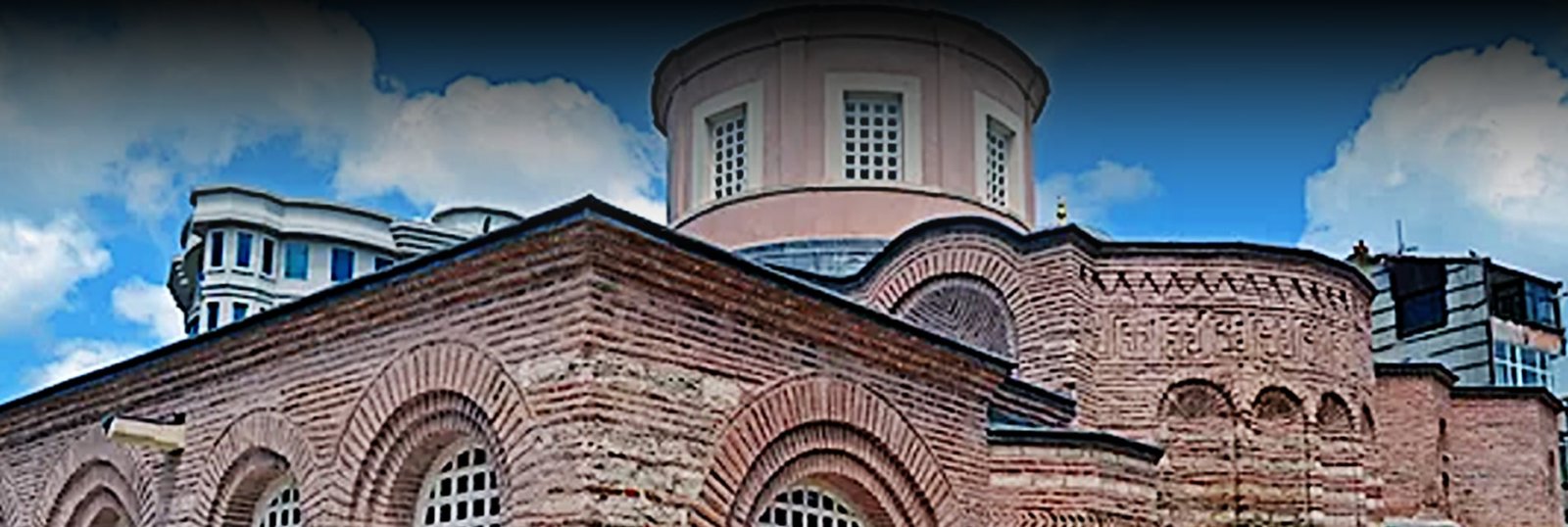

- LIPS MONASTERY © PHOT. wikipedia commons

- LIPS MONASTERY, TRANSVERSE SECTION THROUGH BOTH CHURCHES, BY MAMBOURY © PHOT. Macridy, 1964

- NORTHERN CHURCH, LONGITUDINAL SECTION LOOKING NORTH, BY MAMBOURY © PHOT. Macridy, 1964

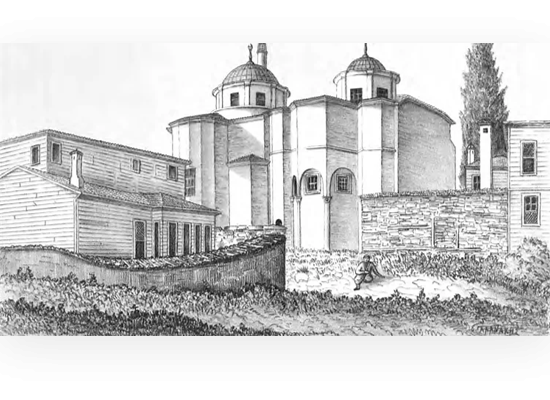

- LIPS MONASTERY, DRAWINGS FROM A.G. PASPATES IN 1877 © PHOT. https://www.thebyzantinelegacy.com/lips

- LIPS MONASTERY, DRAWINGS FROM EBERSOLT & THIERS IN 1910 © PHOT. https://www.thebyzantinelegacy.com/lips

- LIPS MONASTERY, EXTERNAL VIEW FROM S. © PHOT. https://www.thebyzantinelegacy.com/lips

- LIPS MONASTERY, COLOURED STONE INLAY ON MARBLE OF SAINT EUDOCIA, LATE 10TH7EARLY 11TH CENTURY, NOW AT THE ISTAMBUL ARCHAEOLOGICAL MUSEUM © PHOT. Bjørn Christian Tørrissen

- LIPS MONASTERY, INTERNAL VIEW OF THE NORTHERN CHURCH © PHOT. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fenari_Isa_Mosque

- LIPS MONASTERY, INTERNAL VIEW OF THE NORTHERN CHURCH © PHOT https://www.tripadvisor.it/ LocationPhotoDirectLink-g293974-d3746591-i106679595-Fenari_Isa_Camii-Istanbul.html

- LIPS MONASTERY, INTERNAL VIEWS OF THE NORTHER CHURCH DOME © PHOT. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fenari_Isa_Mosque#/media/File:FeneriIsaCamiiInIstanbul20070102_2.jpg

- LIPS MONASTERY, INTERNAL VIEWS OF THE NORTHER CHURCH DOME © PHOT. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fenari_Isa_Mosque#/media/File:FeneriIsaCamiiInIstanbul20070102_2.jpg

- LIPS MONASTERY, NORTHERN CHURCH. RECONSTRUCTED ARCHIVOLT WITH BUSTS OF APOSTLES © PHOT. Macridy, 1964 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fenari_Isa_Mosque#/media/File:FeneriIsaCamiiInIstanbul20070102_2.jpg

- LIPS MONASTERY, NORTHERN CHURCH. RECONSTRUCTED ARCHIVOLT WITH BUSTS OF APOSTLES © PHOT. Macridy, 1964 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fenari_Isa_Mosque#/media/File:FeneriIsaCamiiInIstanbul20070102_2.jpg

- RELIEF FRAGMENTS FROM THE NORTH CHURCH, DATED IN TO 10TH CENTURY (EXCAVATIONS IN 1929 AND 1966) © PHOT. wikipedia commons

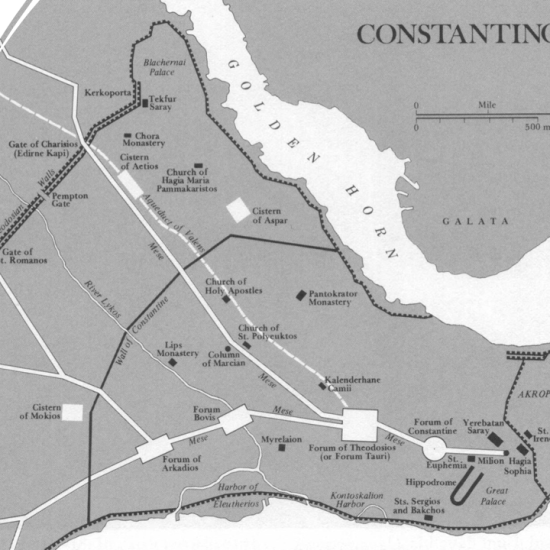

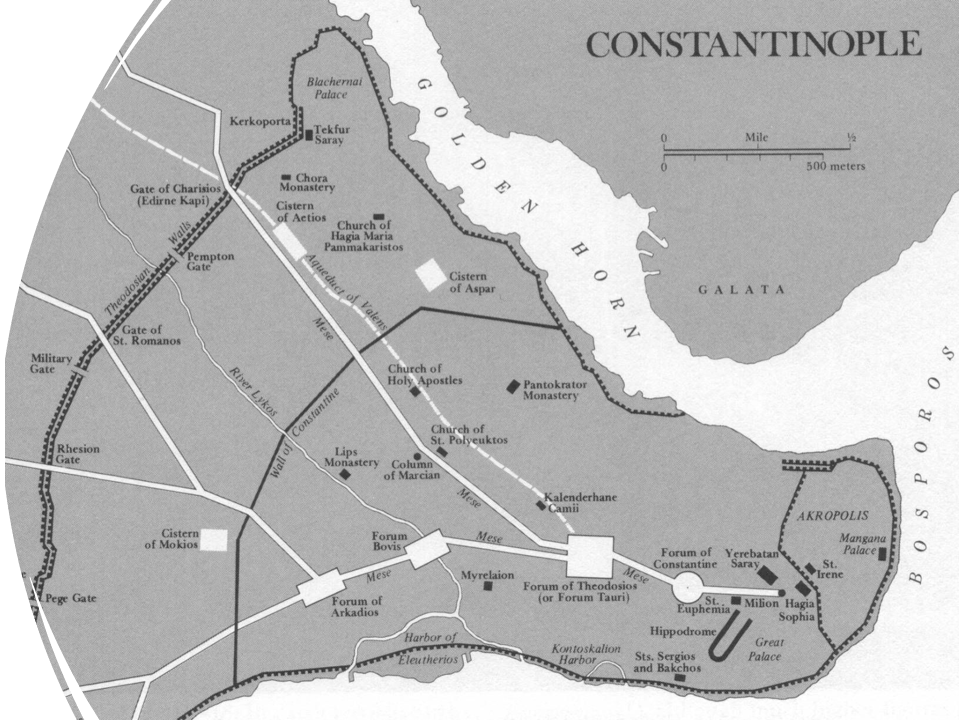

- LIPS MONASTERY IN ITS CONSTANTINOPOLITAN CONTEXT © PLAN. https://www.pinterest.it/pin/569986896575869399/

Tour Location

Lips Monastery

| Other monuments and places to visit | Pammakaristos Church (Istanbul); Stoudios Monastery (Istanbul); Chora Church (Istanbul). |

| Natural Heritage | The city of Istanbul, in the so-called Golden Horn. |

| Historical Recreations | |

| Festivals of Tourist Interest | |

| Fairs | |

| Tourist Office | |

| Specialized Guides | |

| Guided visits | |

| Accommodations | Accommodations in the District of Fatih, as well as in the rest of the city of Istanbul. |

| Restaurants | Restaurants in the District of Fatih. |

| Craft | |

| Bibliography | Hatlie, Peter. The Monks and Monasteries of Constantinople, Ca. 350-850. Cambridge University Press, 2007. Giritlioğlu, Dilara Burcu. ‘An Urban Node in the Ritual Landscape of Byzantine Constantinople: The Church of St John the Baptist of the Stoudios Monastery’. Master Thesis, Middle East Technical University, 2019. |

| Videos | |

| Website |

| Monument or place to visit | Monastery of Lips, today Fenâri-Îsâ-Mosque |

| Style | Remains of Late Antique local masonry structures, later medieval addictions. |

| Type | Monastic complex. |

| Epoch | 907 – 1460. |

| State of conservation | Converted into a mosque. |

| Degree of legal protection | |

| Mailing address | Akşemsettin, Adnan Menderes Blv., 34091 Fatih/İstanbul, TR. |

| Coordinates GPS | 41°00′40″N 28°58′52″E |

| Property, dependency | |

| Possibility of visits by the general public or only specialists | Accessible to general public. |

| Conservation needs | Yes |

| Visiting hours and conditions | Hours when the visit is allowed: 04:30am – 10:00pm. |

| Ticket amount | |

| Research work in progress | |

| Accessibility | Easily accessible on foot, by car or by bus. |

| Signaling if it is registered on the route | Not yet registered. |

| Bibliography | Macridy, Theodore. ‘The Monastery of Lips and the Burials of the Palaeologi’. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 18 (1964): 253–77. Spingou, Foteini. ‘Revisiting Lips Monastery. The Inscription at the Theotokos Church Once Again.’ The Byzantinist, no. 8–9 (2012). Alexander van Millingen, Byzantine Churches of Constantinople. London 1912 Raymond Janin, Constantinople Byzantine. Paris 1964. Thomas F. Mathews, The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul: A Photographic Survey. Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park 1976. Wolfgang Müller-Wiener, Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul bis zum Beginn des 17. Jahrhunderts. Tübingen 1977. Ekaterini Mitsiou, Female monastic space and patronage in Late Byzantine Constantinople, in: E. Mitsiou and E. Kountoura Galaki (eds.), Women and monasticism in the medieval Eastern Mediterranean: decoding a cultural map. Athens 2019, 365-381. Humanities, 2009. |

| Videos | facebook.com |

| Information websites | wikipedia.org byzantium1200.com |

| Location | Located in the Fatih district (Istanbul). |